We’re approaching the halfway point of the 2020 NBA playoffs, our third Game 7 is here, and the East finals start soon.

Let’s bounce around the league for a look at what the postseason has given us and what lies ahead.

1. Predatory Kyle Lowry

With 60% of Toronto’s starting five slumping from the field, Lowry has had to carry an enormous scoring burden against a locked-in defense. That has forced him to tap into a predatory gear that rarely outshines the subtler, more unselfish parts of his game. This is a man normally at ease allowing others to shine — an All-Star who last season drifted into a third-option role behind an apex superstar and a rising young player.

But in this series, Lowry has had to hunt points.

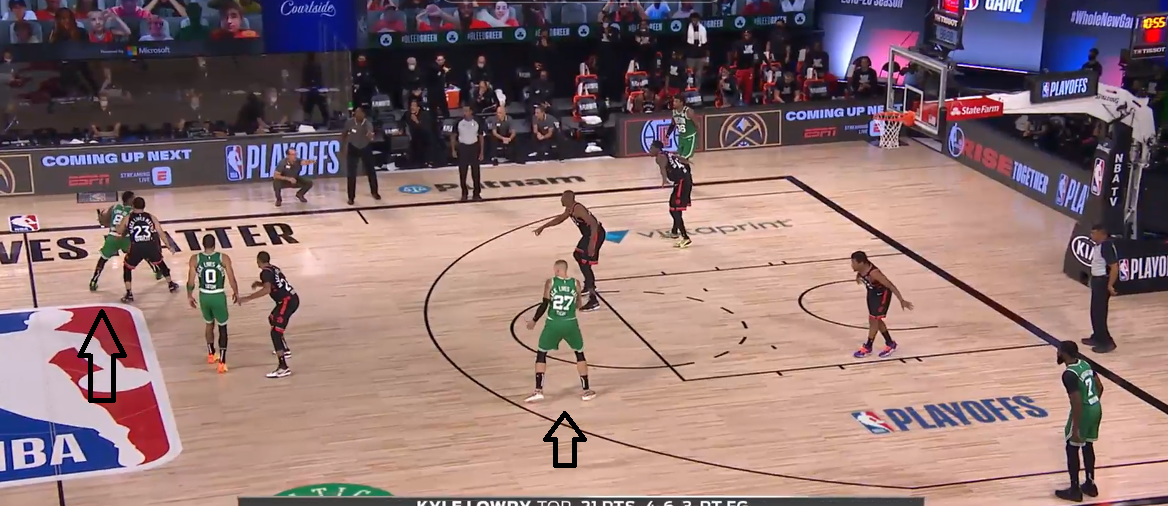

Toronto is running prelude action to get Kemba Walker switched onto Lowry, and Lowry is going at Walker with an eyes-on-the-rim mercilessness that is unusual for him:

(Walker, to be clear, has played some of the best defense of his career in this series. He’s at a strength and, umm, gluteal disadvantage against Lowry.)

Lowry busted out a couple of Mark Jackson/Charles Barkley-style prolonged butt-first backdowns against Walker in overtime of Game 6, leading into delightful turnaround jumpers.

When Toronto has nothing going, Lowry plows into whomever is guarding him:

Lowry is driving 15 times per 100 possessions against Boston, up from about 12.5 in the regular season, per Second Spectrum tracking data. Toronto is eating on those drives: almost 1.2 points per possession when Lowry shoots or passes to a teammate who fires; and 1.375 points if you include all attempts after Lowry drives.

He has been as stout as ever on defense, drawing copious charges, swiping at balls, and stonewalling anyone who thinks a height advantage matters in hand-to-hand combat against a human fire hydrant. (Seriously: the Celtics have barely tried isolating Jayson Tatum on Lowry, and they’re probably smart to be choosy.)

Lowry dug deep for 33 points on 12-of-20 shooting in 53 (!) minutes in Game 6 when the Raptors needed him most. Does he have one more in him?

2. When the Clippers get it popping

A lot of the discourse on Nuggets-Clippers has focused on the Clippers “flipping the switch” on defense, and they have been outstanding on that end save for parts of Game 2. That defense will always be there when the Clippers need it. On some nights against the best offenses, it won’t be enough. Sometimes, great teams just make shots.

The Clippers seize the mantle of championship favorite when they mix in more possessions like this on offense:

The Clippers are an elite offensive team: No. 2 in points per possession for both the regular season and playoffs (and No. 1 among teams still alive). They boast perhaps the league’s best postseason isolation scorer in Kawhi Leonard, and several secondary players capable of creating their own shots. Such talent gives them leeway to slip into malaise for stretches — aimless passing and dribbling, jogging through the paces of their sets.

They can still win those stretches. When Leonard is rolling, LA’s slow-it-down style can be as effective as any glorious passing sequence the 2014 Spurs bestowed upon us.

But when the Clips get the ball popping like that, whoa, baby. (Landry Shamet, featured in the above clip, usually helps the Clippers speed things up.) They become even harder to guard. They toggle between identities — Leonard’s Terminator isolations, and this brand of ball movement — and become more unpredictable for defenses that thrive when they know what is coming.

The Clippers seem to be rounding into shape for the conference finals (provided they finish Denver) — and very likely the Battle for Los Angeles we’re all dying to see. Ivica Zubac keeps improving. Montrezl Harrell snarled and bulled his way to 15 points on 6-of-10 shooting in LA’s Game 4 win. Lou Williams is finding his flow. Doc Rivers is locking into a rotation. The basketball gods owe us a conference finals worth the wait.

3. Nikola Jokic, Everywhere Scorer

We might be one game from saying goodbye to Jokic and the resilient Nuggets, so let’s take a moment to note the big fella has been straight-up dominant on offense for the second straight postseason: 26 points per game on 51/46/84 shooting, plus nine boards and 5.4 dimes. Sheesh.

Jokic has no holes in his offensive game. He is attempting more 3s in the playoffs, which makes the Jamal Murray-Jokic two-man game — a basketball ballet — even more dangerous. Teams often switch in fear of Jokic pick-and-pop 3s, and both Murray and Jokic feast on size mismatches.

I’m not sure how many people realize it, but Jokic is one of the league’s best midrange shooters: 47% on long 2s this season, and 56% from floater range, per Cleaning The Glass. He seems to sense when the Nuggets could use a basket to settle them, and pops for a nice 18-footer instead of a 3-pointer. The triple might produce more points per shot, but the long 2 goes in more often; sometimes a team just needs points.

Blitz Murray, and Jokic slips into open space for one of the league’s softest loping floaters. Jokic has hit at least 50% from that range in three of the past four seasons, and got all the way to 61% — inconceivable! — in 2016-17.

When the Jokic pick-and-pop is tearing a defense apart, you occasionally see opponents dare to put a speedier power forward on him — and hide their centers on Paul Millsap — so they can switch more and run Jokic off the arc. The Portland Trail Blazers tried that with Al-Farouq Aminu last postseason, and the Clippers dabbled in it with Marcus Morris Sr. to open the second half of Game 2 after Denver hung 72 on them in the opening 24 minutes.

Teams usually regret that tactic. Jokic bulldozes smaller guys on the block, and drops very polite layups over them. Double, and you unlock his passing.

Jokic’s defense is a work in progress. The Utah Jazz exposed him and the Nuggets through four games of the first round, but Jokic looked better once the Nuggets got Gary Harris back and played more plus defenders around him.

Jokic and the Nuggets are still searching for the happy medium against the pick-and-roll. Dropping back hasn’t worked; guards finish around and through him. Blitzing is hit or miss, and perhaps too risky against the best passing and shooting teams. There is ground between those extremes, and Jokic looks most at ease there — high on the floor, but perhaps a foot or two below the pick.

Denver is young, with lots of time to figure this out.

4. Eric Bledsoe‘s shot selection

I am not sure if I’ve ever seen someone play as hard on defense for a full game as Bledsoe did with the Milwaukee Bucks facing elimination in Game 5 Tuesday against the Miami Heat. He was hounding his own man, flying around off the ball, emerging from nowhere to get his hands on passes and loose dribbles. It was incredible. We hear talk about “flipping the switch,” but there is a reason guys don’t access that kind of gear until their season is on the line. It’s not sustainable to play that hard for very long.

But Bledsoe’s shot once again deserted him in Milwaukee’s highest-leverage playoff games, and the clanking began before Giannis Antetokounmpo turned his ankle in Game 3. Bledsoe compounded the problem with inexplicable shot selection — long pull-ups early in the shot clock, and whatever this is:

Even normal-temperature Bledsoe is not a good enough shooter to justify those looks. With about 8:50 left in Game 3 and Miami whittling Milwaukee’s lead, Bledsoe dribbled across half court and lazed into a long 3 with 16 on the shot clock — and Antetokounmpo taking residence at the elbow. After a pause to digest what he had witnessed, Reggie Miller on the TNT broadcast sighed, “I mean … Why?” It was the perfect exasperated reaction.

On consecutive possessions where Milwaukee — down 57-56 — had a chance to take the lead in the third quarter of Game 5, Bledsoe bricked a pull-up 2 in semi-transition and then a wing 3 with 16 on the shot clock. Those misses kicked off a scoreless stretch that lasted almost seven minutes and basically ended Milwaukee’s season.

Perhaps there is a relatable human explanation. Bledsoe surely knew he was slumping. The memories of last season’s conference finals loss to Toronto must knock around his brain. Maybe he was pressing: One make, and I’ll feel better — more confident.

It didn’t happen, and now the Bucks enter their most fraught offseason since Kareem Abdul-Jabbar demanded a trade.

5. Russell Westbrook early-clock long 2s

If Bledsoe launches low-percentage early-clock jumpers in search of rhythm and feel, Westbrook probably does so because he believes every one is going in — years of evidence be damned.

Meanwhile, the Lakers rejoice at every shot like this:

Work for something better. The list of shots that are “better” is pretty long.

Westbrook shot 8-of-16 and played with passion in Houston’s otherwise listless debacle in Game 4 Thursday. But he has too often been out of control with the ball against the Lakers, and was the culprit on few missed box-outs during that stretch when Houston made Danny Green look like Moses Malone.

Like many within the league, I was shocked in July to learn how much draft equity Houston had given up — two first-round picks, two swaps — to exchange Chris Paul for Westbrook. It seemed odd to surrender all that to pair Harden with a bad shooter accustomed to hoarding the ball — even if Westbrook is younger than Paul, with a slightly better recent health history.

The Rockets made it work well enough for the most part, though they had to trade another first-round pick (and Clint Capela) to reopen the floor on offense.

Turns out, all the anxiety about the price was justified. Paul was better than Westbrook this season. Houston is on the brink of another second-round exit after Harden’s third 2-of-11 performance in a big Rockets playoff game.

6. Rajon Rondo taking what the defense gives

Rondo is not one of those ballhandling centerpieces who can get everything. Because of his shaky jumper, defenses duck screens and wall off Rondo’s driving lanes.

But Rondo has always been smart about taking what the defense gives him with gusto. One classic Rondoism starts when he brings the ball up the sideline, approaches a pick, and spies the defense setting up to send him toward that sideline. A lot of guards view that coverage as an obstacle to where they want to get — the middle. Rondo has always viewed it as an invitation to sneak baseline and encroach upon the basket:

He doesn’t always start those drives with a concrete plan. He understands the value of simply bringing the ball close to the rim — how it warps the defense, and exposes passing lanes.

Playoff Rondo has has helped unravel the Rockets. He exploded for 21 points on 8-of-11 shooting in Game 3. His ability to throw post entries of all heights and speeds is super valuable on a team with both LeBron and Anthony Davis.

Peak Rondo was a ball-dominant point guard — an old-school conductor with three single-season assist titles. In his twilight next to two superstars, Rondo has thrived as a connector — as I wrote in December. He doesn’t start or finish as many plays as he once did, but you often spot him making the play in between — the extra pass or random cut.

It is the ideal late-career manifestation of Rondo’s unique genius.

Rondo is a polarizing player. On the wrong nights, his bricky jumper can be a hindrance. The Lakers were way better in the regular season with Rondo on the bench. But if you watched the right nights, you could see his value — and it has shown through against Houston.

The Lakers are plus-21 in 112 minutes with Rondo on the floor against Houston — and minus-8 in 80 remaining minutes, per NBA.com. A ton of variables — including random luck — go into any such figure over a small sample, but Rondo’s play has been a big one.

7. Anthony Davis, on the move

Frank Vogel mothballing his centers has cleared the paint and the dunker spots of traffic for Davis and LeBron. There is no center lurking across the lane to smother Davis post-ups. LeBron’s rampages from the top of the arc require long help rotations from the corners — shifts LeBron sees coming a mile away.

But Davis still has to create a lot of tough one-on-one buckets. Even with looser spacing, the Lakers have at times searched for an identity when LeBron rests. One potential catchall mini-solution: getting Davis on the move, in ways beyond the typical duck-ins and back screens for post-ups.

This simple corner action produced clean 3s on two straight possessions in Game 1, and a layup for Alex Caruso in Game 4:

Davis has also looked really comfortable of late going coast-to-coast and sometimes acting as the ball handler in pick-and-rolls:

His volume on such plays has bumped up only a little compared to the regular season, but the Lakers are scoring at a bonkers rate — more than 1.6 points per possession — when Davis-orchestrated pick-and-rolls lead directly to a shot, per Second Spectrum.

In the regular season, Davis drew fouls on 11.6% of the pick-and-rolls he ran as ball handler — the third-highest rate among 255 guys with at least 50 such plays, per Second Spectrum. (No. 1: Bam Adebayo. No. 2: Shaquille Harrison. Man, I wish Harrison developed a jumper. He is so fun to watch — tenacious and ultra-athletic.)

Davis rounds out his game a little every season.

8. The art of the non-screen

An effective pick-and-roll doesn’t require an actual pick — or even the players involved coming within 10 feet of each other. Sometimes setting up for one coaxes the defense into opening up. Fred VanVleet and Serge Ibaka are great at this:

Once Brad Wanamaker angles his body to barricade VanVleet from Ibaka’s screen, VanVleet has a clear driving lane to his right — away from the pick. One hard dribble at Robert Williams, and VanVleet drags both defenders deep enough to give Ibaka an open triple — or force Boston to send a third defender at Ibaka, opening things elsewhere.

Goran Dragic and Adebayo use the same concept to generate violent Bam dunks:

Bledsoe shades Dragic left, away from Adebayo’s looming pick. Dragic happily goes that way — and far enough into the paint to make Brook Lopez commit, decluttering the lane for Bam.

Boston took things further in that epic Game 6 against Toronto; this somehow morphed into a pick-and-roll between Walker and Daniel Theis:

The inventiveness of the league’s best two-man partnerships is really astounding.

9. Lou Williams settling in again

Williams seems sapped of some of his natural purpose when he’s on the floor with both Paul George and Leonard. In those alignments during the regular season, Williams finished only 18.5% of LA possessions with a shot, drawn foul, or turnover — the usage rate of a role player. Williams is no role player (on offense). Wouldn’t the Clippers be better served closing games with a defense-first spot-up type — Patrick Beverley — around their stars?

Sometimes. Rivers will go offense-defense at that guard spot (or two guard spots if he’s playing smaller). He might lean to Beverley when the Clippers have a late lead.

But Williams has hit at least 36.8% of his catch-and-shoot 3s in each of the past six seasons, per NBA.com. He’s useful off the ball. And sometimes, he’ll remind you he can fill an important on-ball role even within the Clippers “A” lineups — including on this clutch layup in Game 3 against Denver:

There is obvious value in a ball handler who creates catch-and-shoot looks for George and Leonard. But giving the ball to Williams also works as a way to attack both the opponent’s weakest defenders at the same time — i.e., Murray and Jokic above. There is no place to hide against LA.

The Clippers will also occasionally have Williams screen for Leonard, or vice versa — a method of engineering mismatches. (A bunch of Leonard’s highest-volume games as a screen-setter have come in the postseason, though that is partly the result of an uptick in his minutes.)

Playing Beverley and Williams together when one of Leonard and George rests provides nice offense-defense balance. The Beverley-Shamet duo leaves the Clippers a little light on ballhandling when George is the solo star. Rivers against the Nuggets has split Williams’ minutes pretty evenly between playing with Leonard only, George only, and both. I’d think about reorienting them (if it’s possible) more toward the George-only minutes, since Leonard is more at home than George as undisputed lead ball-handler.

These are happy problems for a coach.

NBA schedule: Game 7, plus the West semis