As the world waited for Primoz Roglic to appear over the summit approaching La Planche des Belles Filles on Saturday, resplendent in yellow, they expected something special.

This was a man who had spent three weeks demonstrating he was at the peak of his physical power, complete with mirrored sunglasses and a chiselled jaw, stylishly negotiating 3,000km of French countryside behind his all-powerful Jumbo-Visma team.

They got the opposite. A shell of a man, garish in yellow, sunglasses gone, panicked eyes visible instead, helmet lop-sided – a vision, almost, of a distressed child riding a bike too small for him.

It had to be one of the saddest sights in modern sport. Almost Samson-like, shorn of his powers. The colour drained from his face.

The beneficiary was 21-year-old fellow Slovenian Tadej Pogacar, who had been the only man to hang on to Roglic and his team’s coat-tails for the previous 19 stages, making him the second youngest, and most unexpected, Tour de France winner since World War One.

It was an outcome that turned a highly entertaining race into a stone-cold classic.

The overarching reason may well be that a young lad started a minute behind in a time trial he was expected to be beaten in, and finished it a minute ahead after riding with a team – UAE-Emirates – who had lost two of their members earlier in the race, and who run on a far more modest budget those they beat.

A finish like that brought comparisons to the Tour of 1989, won by Greg LeMond in Paris on the final day by eight seconds after he beat Laurent Fignon in a time trial – Fignon and Roglic adopting very similar sitting positions on the tarmac, pictures of disbelief 31 years apart.

But what was more startling was the dramatic downturn in form of the two pre-race favourites, Roglic and Ineos Grenadiers’ Egan Bernal.

When was the last time a defending Tour champion just stopped halfway up a mountain halfway through a race? Or someone of Roglic’s form suddenly fell apart metres from the end?

It never happened to Chris Froome…

How badly did Ineos get it wrong?

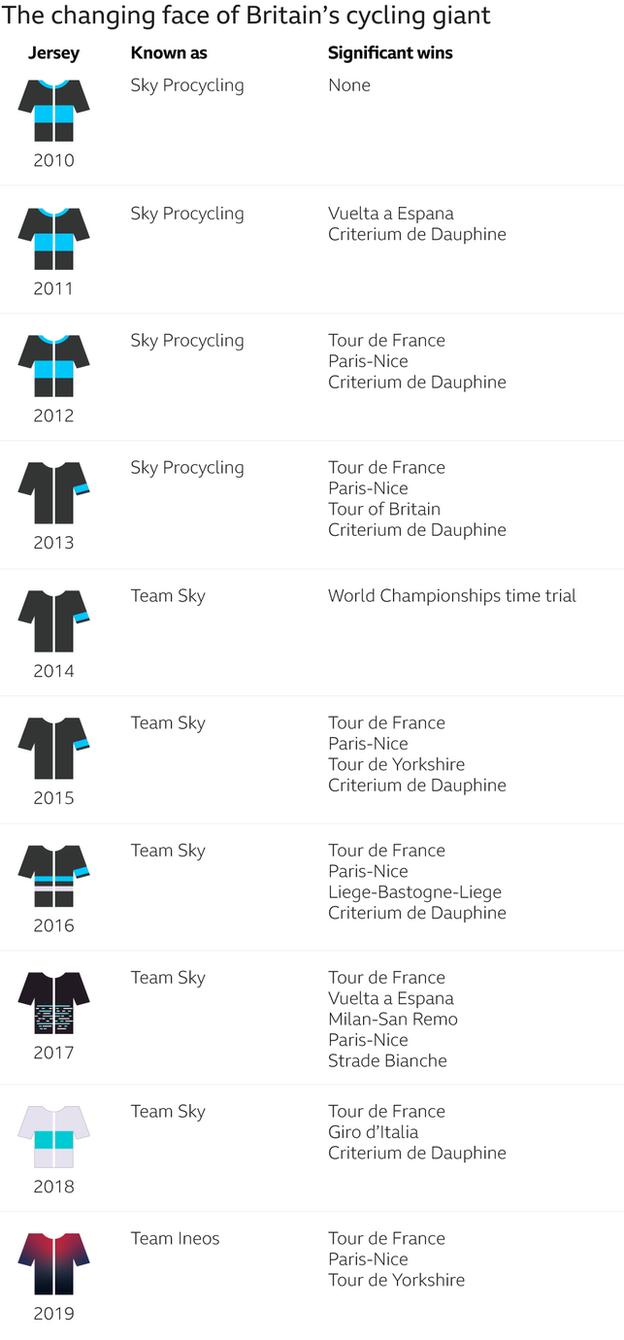

So, what of Bernal? The defending champion who shocked the sport a week earlier by inexplicably capitulating on the Grand Colombier during stage 15 for a team who have won the Tour in the seven of the past 11 years.

“I have taken my body to the limit – there’s comes a point where it has told me: ‘enough,'” he tweeted.

Bernal is a charming and honest character, who even cut his own hair during this Tour because he was bored sitting around in his ‘bubble’. Much to the bemused delight of his team-mates.

But if the rider is at a loss as to why his form deserted him – and he genuinely is – then is it the fault of his team?

Ineos Grenadiers boss Sir Dave Brailsford has been in the spotlight after what was, for some, a controversial decision not to take four-time winner Froome and 2018 victor Geraint Thomas to the Tour this year.

Plenty have criticised his decision to take such an inexperienced pair in Bernal, 23, and second protected rider Richard Carapaz, 27.

But, by their own admission, the rejected riders did not have the form to take into the Tour, especially not in comparison to Bernal – who was in blistering form during the first two of three warm-up races which directly informed the team’s decision on who to take.

It’s all in the mystical numbers that each rider is ‘putting out’. If Bernal was posting the performance metrics, such as watts per kilo, the team needed him to (which he was) and his form was better than all the other leaders during the warm-up races (which it was), then how can someone in Brailsford’s position at any team possibly know their top athlete would lose his form so quickly?

It just doesn’t generally happen in top-level road cycling.

But if nothing else this can serve as a wake-up call, and as one team member put it: “I think there’s been real pride at the way we fought in the final week. Obviously overarching disappointment, but there’s lots of Grand Tour racing to come this year and excitement about rebuilding and improving for next year.”

A year that will include Britain’s star turn at this year’s Tour Adam Yates appearing as an Ineos rider – he spent four days in the yellow jersey for Mitchelton-Scott, despite a pre-race illness.

Add to that the possibility of young British hope Tom Pidcock bringing more homegrown talent to a British team, whose owner – industrialist Sir Jim Ratcliffe – is very keen to promote that as part of its identity.

Thomas, of course, will have a chance to show what he can do for Ineos at the Giro d’Italia in October. The team are yet to decide who will support ‘G’ in Italy in what could be a treacherous race in the Italian Alps as winter approaches, but Tour failures put more focus on that race.

Froome, still thought to be much further from top form than Thomas, heads for team leader status at the Vuelta a Espana towards the end of October with a chance to show his mettle.

Froome, for all the injury, contract and form drama, could still be Brailsford’s darling in 2020.

Oh, the irony.

So many casualties

If Bernal’s demise cannot be explained, what on earth happened to Roglic?

“I just didn’t push enough,” he said. “It was like that. I was more and more without the power I needed but I gave it all until the end.”

So another inconclusive assessment…

Since bursting on to the scene in a 2016 time trial, he has been a very solid performer, gradually building up to team leader status, always with Jumbo-Visma, who seemed to grow in stature and budget alongside him. Roglic came into this race after winning the last Grand Tour – 2019’s Vuelta a Espana.

So he was strong coming in, and despite a crash during the Criterium du Dauphine showed no signs of the loss of performance that befell him on Saturday.

Other team leaders also suffered – and some far earlier than they had previously. France’s big hope Thibaut Pinot fell away painfully early during stage eight. No fireworks, no injuries, no adversity – he just started to go slowly and had no answer.

The one thing all riders have had to contend with this year is the season’s delay because of the coronavirus.

By spring warm-up race Paris-Nice the whole sporting calendar was closing down, as did most riders’ ability to train outside during lockdown – especially in Monaco and Andorra, the tax-haven heartlands of the European World Tour cyclist.

Bernal, it should be noted, was stuck in Colombia during this time – and some suggested was benefiting from an ability to get on his bike more frequently than his home-bound rivals.

If this most brutal of sports carves the body in unnatural ways, maybe it even dictates the time of year riders can be expected to achieve optimal performance – meaning Bernal, Pinot, Froome, Thomas, Roglic, et al would be far more consistent in the middle of July than as autumn approaches.

Coping with Covid

Organiser ASO will look upon this Tour as a successful pilot for bringing fans back to major sporting events – thousands lined the roads in cities and on mountain summits, even though many believed they would be stopped.

It is hard to see how anyone can prevent people from climbing through alpine trees if they are that determined. And determined they were – so much so that the fancy dress hordes seemed closer than ever to the riders’ faces on the tops of the climbs, leading some to plead with them to stay away.

ASO’s approach has been a success, but it wasn’t without risk: two pre-race tests were followed by just two more for all riders and staff during the three-week race, taking place on each rest day. Apart from that a daily questionnaire and temperature check was all that was applied.

But what if someone was asymptomatic? And so it proved with at least six team members sent home across the course of the race. Surely all it took was one asymtomatic person to transmit the virus through one team ‘bubble’ and the whole peloton was at risk?

No riders were infected, at least since last Monday when they were last tested.

But if the coronavirus didn’t prevent the race reaching Paris, then another danger did for one rider at least – and it is one the UCI might do well to look into.

Plenty of riders abandoned during the event – usually as a result of broken bones and complications following a crash out on the road. In Lukas Postlberger of Bora-Hansgrohe’s case, it was a wasp sting inside the mouth.

France’s other big hope, AG2R La Mondiale’s Romain Bardet, was having a great Tour, just 30 seconds down in the general classification when he crashed on stage 13, striking his helmet harrowingly hard on the tarmac.

After an assessment lasting a few seconds that included a moment when his legs buckled underneath him, it was decided he was fit to continue to climb up to Puy Mary Cantal and finish the stage. Where he was promptly diagnosed with concussion and given a scan that revealed a “small brain haemorrhage”.

Given the seriousness of the injury, it is shocking there are not more strict protocols in place to prevent riders from putting themselves under physical duress while in a dangerous medical state.

As the UCI states itself in its ‘concussion and return to competition’ medical rules: “Any rider with a suspected concussion should be immediately removed from the competition or training and urgently assessed medically.”

As promising young Ineos domestique Pavel Sivakov put it just before embarking on this Tour – and suffering at least three crashes himself during proceedings – “cycling is not an easy life”.

And Roglic, who showed grace in defeat by embracing Pogacar immediately after picking himself up off the tarmac, would echo that sentiment.

Sunglasses back in place, the swagger on the bike even returned on the Champs Elysees on Sunday – 24 hours after one of cycling’s biggest chokes, he is ready to go again.