Juan Jose Florian’s childhood home was in a clearing hacked from the Colombian rainforest. His family earned a living by growing papayas, oranges and avocados. But at night the region belonged to illegal armed groups.

Those who defied the curfew they enforced were taken, tightly bound, and either left for the night or, if they were repeat offenders, executed. Bodies turned up daily on the forest paths.

There were no real roads, no television. Where other children followed football teams, Florian and his elder brother Miller would sneak out and watch the tracer fire that lit up the night sky, cheering on the Colombian army in their conflict with the Farc – the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – and other rebel groups.

“When the army was there, we could play outside until late, and the schoolchildren were safe from forced recruitment,” Florian says.

Guerrillas with the Farc – founded in 1966 and disbanded in 2016, when they signed a ceasefire – were regular callers at the family home, demanding food, money and more.

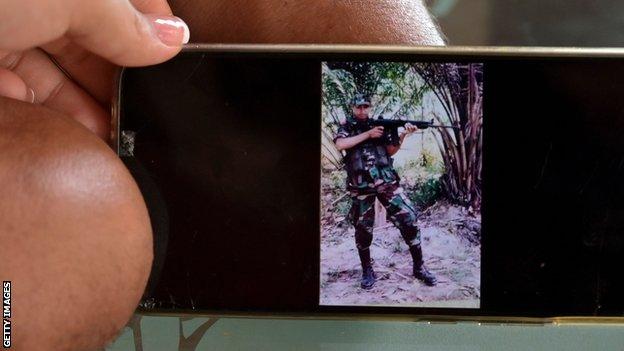

Both Florian and his brother Miller resolved to become soldiers when they grew up. When Miller was 23, he travelled to the nearest town, presented his documents at a checkpoint and was told he was long overdue for compulsory military service. He did not complain.

Some weeks later, a band of Farc soldiers visited Florian’s family in their isolated forest clearing with a message. The family had given a son to the forces of reaction, they said, so they owed another to the revolution.

“My mother tried to fight them. She pleaded with them. As they led me away, she blessed me through her tears,” says Florian.

In this way Florian – aged 16 in 1998 – was dragged into a conflict that killed 260,000 people and left more than six million internally displaced between 1954 and 2016, on the opposite side to his own brother. He was one of over 18,000 minors, 70% of them younger than 15, recruited by the Farc during their five decades of armed struggle as the country’s largest rebel group.

“We were subjected to hours of psychological pressure,” Florian says. “The values they taught were the opposite of my mother’s. I was always thinking about my escape. I spent my days looking, listening, planning. I saw how deserters were shot for betraying the cause.”

But Florian resisted their indoctrination and, a year into his life as a child guerrilla, he saw his chance for escape.

His battalion, the 27th Front, was sent to attack a police station. The army sent in helicopters.

“They spotted us and fired,” he says. “I hid under the canopy of a tree. As a helicopter circled above me, I shuffled around the trunk.”

As his companions fled, Florian burst into a farmhouse, catching the occupants – a man and his wife – unawares.

“There were lots of Farc sympathisers in those parts, and they received a bounty if they handed in deserters, so I said, ‘One false move and I’ll shoot.’

“I told them I needed clothes. The man gave me jeans and a white shirt. I made him and his wife get down on the floor and, with my one free hand, I changed out of my fatigues. I told them not to get up and I ran out of the house.

“I found an army roadblock, threw away my rifle and approached. I told the officer that I was a guerrilla and wanted to turn myself in. I told him I hadn’t eaten for two days. They gave me food and I told them my story. They asked me what battalion my brother was in. Fortunately my brother had reported my forced recruitment, and they confirmed that I was who I claimed to be.”

Florian was placed under army protection in the capital Bogota.

“I was afraid to go out in the street in case they found me,” he says. “It was terrifying. I was so young and I had such a big and powerful enemy.”

Back at home, his mother had to flee the farm with her other children, whom she sent to boarding school for their safety.

When Florian turned 18 in 2000 he joined the Colombian army. After his training he spent 12 years fighting campaigns against drug gangs and fuel smugglers. His brother Miller continued his own military career, only to suffer tragedy in a shootout with the Farc in the town of El Dorado, Meta, about 350km south-east of Bogota.

“It was a very confused operation in which he shot and killed a man,” Florian says. “When they went to identify the body, it turned out he had shot his best friend. It hit him very hard. He went into shock.”

Miller began to show the signs of chronic paranoid schizophrenia. Florian travelled home on leave to see him. Their mother had sold the farm, and refused to pay a so-called tax demanded by the Farc. They had tracked her down to her new home. On 12 July 2012 a package appeared in the yard.

Florian says: “I remember seeing something by the door. I walked towards it, squatted and reached out my hands. The next thing I recall is lying on the ground screaming. Both of my arms had gone.

“My right leg had been torn off above the knee. I had second- and third-degree burns everywhere. My right eye had gone, and I had lost hearing in my right ear. My brother was cradling my head, and I was shouting, ‘Kill me. Shoot me. I can’t live like this.’

“He stroked my head and told me, ‘Don’t ask that of me. You’re going to be OK.’ I was screaming insults at him to try and make him angry. Then I passed out.”

Florian woke up after 12 days in a coma. Months of operations and skin grafts followed. His emotions were swamped by depression, hallucinations and thoughts of suicide.

“I considered throwing myself out the window or down the stairwell,” he says. “But I thought, ‘What if I fail, and end up even worse?’ I decided to learn to walk so that I could jump in front of a car. But in the end I came to the same conclusion: what if I survive?”

After months in intensive care, and endless expressions of sympathy, he had the good fortune to be transferred to the Private Jose Maria Hernandez Battalion, a special corps in the Colombian Army for those traumatised from the conflict.

“I was sick of being pitied, but I found myself in a place of laughter and brotherhood,” Florian says. “The other soldiers looked at me and called me ‘Quarter Chicken’. They touched my stumps, they laughed at me. We threatened each other with fist fights, but no-one had any fists! In their company I came back to life.”

As part of his treatment, Florian began hydrotherapy. The group sessions quickly became competitive.

He found he could hold his breath under water longer than his colleagues, and beat them over a length of the pool. He started to time himself and improve on his times. In the pool he met civilians injured in road traffic accidents or affected by degenerative diseases, competing in Bogota’s Para-Swimming League. Florian began to swim for the military team.

“Some of my friends spent their lives drinking to stave off the pain. I wanted a different life,” he says.

“I began to swim greater distances. With the few limbs I had left, my ambition began to grow. In Para-swimming, there were no obstacles, no barriers, no discrimination. I was coming from a psychiatric treatment where I depended on medication for my sleep and my peace of mind. Swimming got me off my medication. Or rather, swimming became my medication.”

Florian won his first medal in the United States at an event organised by the University of Minnesota in 2013. For three years he competed in the S5 butterfly class, breaking records all over Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, the US and Canada.

He won his last medal at the national games in 2015. The following year, four years after the explosion, he was pensioned out of the army and started a university degree in psychology. No longer able to compete in the military Para-swimming team, he decided to pursue another sporting ambition.

“My stepfather, the man who brought me up, was obsessed with cycling, like most Colombians,” he says. “During the Tour de France, the Giro d’Italia, the Vuelta a Espana, he always had a transistor radio to his ear, listening to the race.”

Still, Juan had never ridden a bike, even as a child.

“And I thought I never would. I assumed you needed arms, legs, good eyes, good reflexes,” he adds.

But curiosity got the better of him.

“Someone had given my sister a bike to get to work on. I took it into a back street with a friend, tied the stumps of my arms to the handlebars with rope, and set off.

“I thought I would lose my balance and topple over sideways. In fact I had thousands of thoughts, all of them negative. But the moment I got on the bike and pushed the pedal with my good leg, I realised that I was wrong. I said to my friend, ‘Let go!’ I rode up the street, turned round, and came back again, and shouted ‘I can be a cyclist! I can be a Paralympic cyclist!'”

Florian’s wife Angie set about helping adapt the bike further. She used power tools to turn metal sheets into buckets for the stumps of his arms, but it caused him back pain and tendonitis. He appealed to the national sports authorities for assistance. In vain.

“In Colombia, the Paralympic system is more open to professional athletes who have suffered very minor disabilities than triple amputees. We are regarded more as a potentially expensive problem, or as patients in rehab,” Florian believes.

He found the solution himself in December 2017.

“I was invited to give a motivational talk at an airbase in Colombia’s coffee-growing region, where the Air Maintenance Corps of the Colombian Air Force is based. They wanted me to tell them a little bit about my life story and what I was doing every day.

“Chatting with the engineers, I discovered they were experts in aerodynamics and worked with carbon fibre. I asked if they could help me modify my bike and they said, ‘We’ve never worked with bikes, but let’s do it!’

“They took some ideas from their usual work, some of my ideas, and we began working on weight, aerodynamics, everything.”

Florian thinks he has more amputations than any other C1 cyclist in the world. His injuries pose enormous difficulties for bike designers. Even so, the aircraft engineers took an 18kg bike, adapted it using state-of-the-art carbon fibre and reduced the weight to 8.5kg.

By holding raffles and adding voluntary contributions and small sponsors to his army pension, he funded trips to World Cup events in Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands, and World Championships in the Netherlands and Portugal.

In 2019 the telecommunications firm Movistar Colombia began to sponsor him. Nationally famous, he took on a Superhero soubriquet.

“In Colombia, people with amputations are called mochos. When I started cycling, I said to myself that if we have heroes like Superman or Batman, why can’t I be Mochoman?”

With only three places for Para-cycling and a long list of eight riders, Florian failed in his bid to go to the Tokyo Paralympics. But he took it philosophically. “I’m still alive and there’s another Olympics coming,” he says.

Now 39, in November this year he was crowned Colombia’s national Para-cycling champion – in the road race and time trial.

And he has a new target. Already an accomplished swimmer and cyclist, Florian has the goal of racing an Ironman triathlon. He calls the bomb that nearly killed him “a gift of life and my second birth”.

He says: “I’m in the process of running, jogging, and I’m very excited. I don’t have a special prosthesis or have a medical team to support me but, with the people I have, we are going to start working on it.

“I want to show the world that you can fulfil your dreams. It’s not just about rehabilitation; it’s beyond that. In the soldiers and policemen we lose to armed conflict, we are wasting a wealth of human talent, often lost to drink and drugs.

“I want to be the voice demanding that the country give its wounded soldiers more opportunities.”