Off a long, straight road in Alicante province, Mark Cavendish sits in a dusty valley, smiling with team-mates during a break in the day’s training among the jagged hills and orange trees of eastern Spain.

It’s unseasonably warm and windy for January, but Cavendish’s obvious high spirits rise above the continual gusts – as well as the Flemish retorts of his fellow riders. There’s joy on his face – no hint of the horror of the November burglary at his home in Essex, or the broken ribs and a collapsed lung sustained in a heavy crash at a track race that same month.

He is small in stature next to several of the powerhouses who aid his work for the ebullient Belgian Quick-Step Alpha Vinyl team, and he sits on the edge of the throng, but he is the patriarch. You can just sense it – born out of his success as cycling’s greatest sprinter.

Last July, Cavendish triumphed four times at the Tour de France to bring himself level with Eddy Merckx’s record 34 stage victories. At the age of 36, it was one of sport’s great comebacks.

Cavendish had not won a Tour stage for five years. He’d suffered setback after setback, season after season. Injury, illness and depression combined as he considered retirement in late 2020. It was an emotional return and one that resonated strongly among cycling fans.

“It was the first time that… as a sportsperson you’re disassociated from a human point a lot of the time. It was the most connected I felt in my whole career, to the fans,” Cavendish says. “They’re not watching you do something – they’re living it with you.

“All I can say is the biggest joy I got from 2021 was people saying ‘thank you’. I haven’t really heard that before – I would get ‘well done’ or ‘congratulations’. But I got ‘thank you for the joy and hope you give us’. It’s touching, you know.

“I’ve had some hard years, but a lot of people have had worse years. I hope I can give hope that… if you push hard enough anyone can come back and stand on the top step or whatever you want to.”

Patrick Lefevere, his team’s manager, said what happened last summer was “a miracle”. But he also knew just how determined the Briton had been with his training throughout the year. Cavendish, who turns 37 in May, has to be the hardest working man in cycling. Often, he’ll make sure everyone else is working just as hard. He can be fiery when frustrated.

“When he steps out of the team bus you never know if he’ll come back in five minutes like a wild bull because something is wrong with the bike,” smiles Tom Steels – a former sprinter himself and directeur sportif for the team during last year’s Tour.

“But you can always talk with him and once it’s fixed it’s over. It’s not ever personal, but you never know how he can react.”

Later, with the day’s training complete, Cavendish is surrounded by journalists, athletes and coaches in a large room that resounds with chatter. He is unhappy, and everyone knows it. He’s been asked whether he will be going to this year’s Tour de France. Again. It is another source of frustration.

For some he might seem a shoo-in for what could perhaps be a last chance to set a new record with a 35th victory. But it’s not that simple. Last year he was only included after injury to since-departed team-mate Sam Bennett. And once again the competition will be fierce.

Getting another shot will be no mean feat. But it has never been simple for Cavendish. It’s what’s made him who he is.

Sprinters might be described as the rock stars of cycling – the most gladiatorial and combative riders. Cavendish could be Liam and Noel Gallagher rolled into one; an acerbic, inaccessible hero with a brooding wisdom and a sharp wit that will catch you off guard. His uncompromising attitude has always stood out.

“Mark is Mark and he won’t hold back his emotions. If he is angry he will say it,” says Lefevere, who is himself known to have cut a few journalists down to size.

“I think he has a lot of emotions, and emotions drive him – but it mustn’t hide his huge talent. Don’t forget this.”

Cavendish’s talent first showed on a BMX, growing up on the Isle of Man. Sitting in the Irish Sea between north-west England and Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man is where each year they race the world’s fastest motorbikes at 200mph between dry stone walls. “It’s in the blood,” Cavendish says.

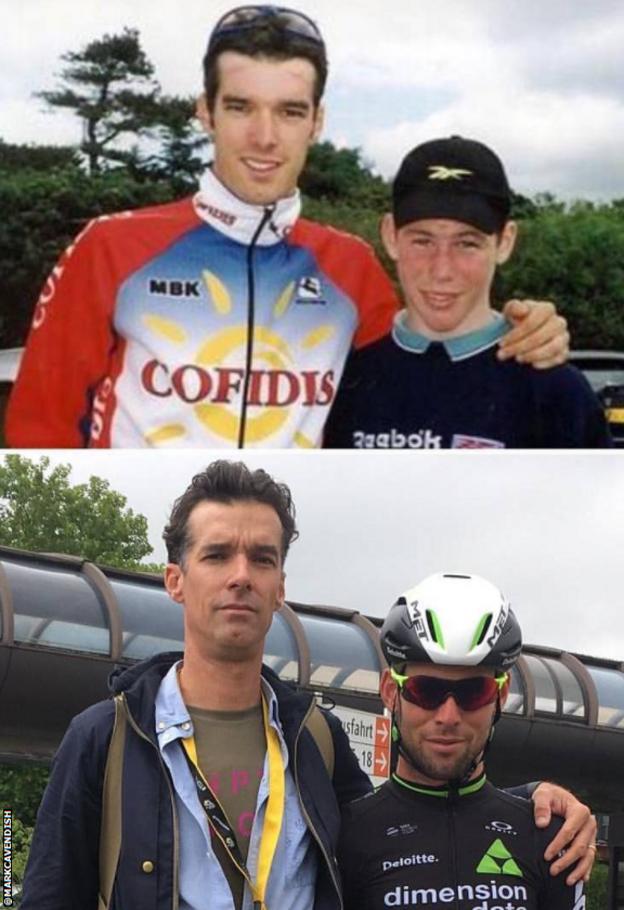

There is a photo of a 14-year-old Cavendish at the Tour de France of 1999 with one of his idols, the now-retired David Millar. Two years later the youngster had left school to work in a bank, with the goal of earning enough money for a tilt at becoming a professional cyclist in Europe.

He did just that. In an extraordinary era of the purest of pure sprinters, Cavendish earned the nickname the Manx Missile as he began to show his full potential within a peer group of the punchiest, most physically aggressive riders, such as German rivals Marcel Kittel and Andre Greipel.

They would jink and twitch on the tarmac, gambling on the correct line to launch themselves towards the finish in a furious release of energy, a brutal miracle of fight and flight at speeds close to 80kph.

And Cavendish notched up more Tour stage wins than them all – winning 30 times between 2008 and 2016 for HTC Highroad, Team Sky, Etixx-Quick Step and Dimension Data.

Unlike 100m sprinters in track and field – who know their lane is their own – cycling’s sprinters know each battle could end in a horrifying crash, just as it did for Cavendish at the 2017 Tour when Peter Sagan’s elbow was used as a blocking tool. Sagan was disqualified and Cavendish was forced to withdraw with a broken shoulder, having been forced into metal barriers.

The bone healed. But looking back, that moment seemed to signal a shift in his competitive spirit. What followed was a journey to the depths of despair.

Cavendish returned for the 2018 Tour but missed the time cut on stage 11 and was eliminated. An explanation as to why came a month later when he was diagnosed with the Epstein-Barr virus, which causes glandular fever. It had rinsed him of the energy needed for elite competition and training.

A period of “total rest” followed, but when an uncharacteristically subdued Cavendish did return he suffered some bizarre crashes. First came a huge somersault when clattering into a traffic island during the gruelling Milan-San Remo. Then he came to grief behind the commissaire’s car before the Abu Dhabi Tour had even officially begun.

A change of teams from Dimension Data to Bahrain-McLaren in 2020 didn’t help, and by the end of a Covid-affected season he declared through tears at the Gent-Wevelgem classic in Belgium that he had contested “perhaps the last race of my career”.

There would have been no shame in retiring then. Cavendish was already the second most successful at winning stages in Tour history, a green jersey winner and world road champion in 2011, an Olympic silver medallist and a three-time world champion on the track.

But he did not step away. And his old boss Lefevere was watching.

“The situation of more than a year ago, he looked desperate on the TV,” the Belgian says.

“I saw it and I thought: ‘No, that cannot be true.’ I called and he came to my office and we found a last-minute deal; everything went like a train.”

It’s fair to say only a few watched the first real signs he was back to his best.

At a miserably overcast Tour of Turkey in April 2021 – which virtually no riders wanted to attend because of spiking coronavirus cases everywhere – Cavendish won four of the eight stages. The joy and relief was clear, even if he was up against those considered second-rate opposition on the World Tour.

“He was there and he won his first stage and we had a Facetime call and he started crying,” remembers Lefevere.

“It was the best moment. I got off the phone and said ‘Now we’re going to drink Dom Perignon’, because then I understood [he was back].”

Two months later came another big twist.

“Bennett was always the sprinter for us,” Lefevere continues. “But then his injury came in June. At short notice we put Mark in at the Tour of Belgium. He was in London and flew over in a helicopter two hours before the start, and he won a stage.

“When it was clear Bennett couldn’t do the Tour either, I called Mark and he said: ‘Patrick, you cannot think what I am thinking. My suitcase has been ready for two weeks and I’m nervous like a junior.’ That’s when I understood he would be doing a great Tour.

“When he won [his] first stage, I think that was one of the biggest emotions I ever saw in 20 years of my team, with everybody. And then the miracle happened; one stage became four and then the green jersey.”

Cavendish’s comeback was particularly remarkable for an endurance sport, where form and physical output numbers rarely show an upward turn as age increases.

The victories, the tears and the tantrums – the 2021 Tour de France saw it all from Cavendish. And the fans want it all over again.

But even during the build-up to last year’s final stage in Paris, where he missed out on a 35th win by finishing third, he never seemed too bothered about the record when asked about it. It was just the sheer joy of competition driving him.

He is too modest to try to decipher why he is so popular both with young lads who want to emulate him – “he was my idol growing up, and now he teases me as he does everybody in the team, he’s great to have around,” says 21-year-old fellow British sprinter and room-mate Ethan Vernon – and with an older generation of female fans who saw Beryl Burton ride in the fifties, all of whom gravitate to a sportsperson with the most admirable of qualities: spirit.

Whether we will see him at this year’s Tour is not yet known. No matter how high your status in your chosen field, everybody has a boss.

“I’m not Madame Soleil, I don’t have a crystal ball,” says Lefevere. “Last year nobody knew Mark would come to the team, let alone compete at the Tour, or win four stages.

“In my opinion the best riders always go to the best competition.”

Steels adds: “He is a leader, with his British humour. He creates the team around him – but he does it in a natural way, he doesn’t force anything. Yeah, sometimes he’s a firework, but only 10 minutes of fireworks and he calms down again. Well, let’s say 10 to 20 minutes… and then he’s there.

“I think he gets a lot of power out of the battle. For me he is the best sprinter that ever was in cycling.”